What I Have Learned While Building Finance Functions from Scratch

The Art of Right-Sizing Your Finance Function: Lessons from the Trenches

After spending most of my career in FP&A working in Fortune 500 and Publicly Traded companies, I thought I knew exactly how to build a finance function from scratch. I was wrong. Dead wrong. Here's what I learned about right-sizing financial operations while serving as a fractional CFO for an early-stage startup.

The Three Horizons of Financial Planning

Traditionally, finance teams look at three time horizons:

Short-term (e.g. 13-week cash forecasts)

Mid-term (e.g. 12-18 month financial statement forecasts)

Long-term (e.g. 3-5 year strategic plans)

While all these horizons matter, I made a classic mistake: I treated our startup like a mature business instead of the scrappy venture it was.

I had fallen into a trap.

The Over-Engineering Trap

I was building across all three time horizons because that’s what finance does. But here’s the problem, the startup was in business model verification mode, which made instituting these practices difficult for a number of reasons:

Things were changing so rapidly that when we tweaked the business model, those changes rippled through three planning timeframe, making the models more challenging to manage than they needed to be.

This pace of change also increased the opportunities for errors

Cash management was paramount because when you run out, the gig is up anyway, so who cares about three year P&L projections with a nine month runway?

Of course, long-term planning has its place in startups—after all, you need growth projections to pitch your vision to investors. But this shouldn't be your primary focus.

Picture this: I'm sitting there with a team of five people and 50 customers, implementing:

Sophisticated forecast policies

Investor pitch decks

18-month cash flow projections

Regular expense reviews

Monthly financial deep-dives

I had brought my Fortune 500 playbook to a pickup basketball game. The team didn't need - and frankly couldn't sustain - these enterprise-level processes.

I was also obsessed with promoting AI solutions for our processes. Despite our small team and limited resources, I believed AI tools could help us bypass traditional constraints. I spent time meeting with AI vendors, discussing ways to streamline our sales cycle, speed up lead qualification, and improve lead quality.

Sounds great right??

Not really. These B2B platforms were far too expensive for our limited budget, especially with our burn rate concerns. Plus, we hadn't even validated our business model yet.

What good would an AI-powered sales team do for our billion-dollar aspirations when we were only handling five leads per week? The costs and effort simply didn't justify the potential benefits.

I had lost sight of our immediate needs, fixating instead on processes and systems we might need three to five years down the road.

What Early-Stage Companies Actually Need

In retrospect, I should have focused on just three core areas:

Cash is king - reporting should’ve revolved around cash flow

Basic reporting through QuickBooks was working fine. While this could be automated for monitoring, our key focus needed to be answering three critical questions: "What's our cash balance?", "What's our burn rate?", and "How can we either slow the burn or raise more cash?"

Customer metrics - focus on LTV and core billing/onboarding analytics

Like most startups, the company was obsessed with growth, but the systems managing that growth needed to be robust. We onboarded customers that we analyzed would be profitable based on their profiles. We effectively vetted these customers after launch to verify they met our model's expectations—and when they didn't, we adjusted the model to reflect reality.

Beyond that, our systems needed to be focused on three critical aspects: ensuring customers were billed on time, confirming they paid on time, and alerting us when either process went off track. I wish we would have spent more time on this.

Investment requirements - but only through the lens of the above two areas

Every spending decision was essentially a strategic investment from our cash reserves. While these decisions were typically based on gut feelings from the heads of sales and operations, the finance department should have provided these stakeholders with a framework to ensure our investments would:

Improve the cash position

Make customer acquisition, onboarding, billing, and collections more efficient and profitable

Without clear proof (or at least a compelling argument) that the investment would accomplish one or both of these goals, we should have passed. Finance's responsibility was to establish these decision-making frameworks.

Everything else was just window dressing. Those beautiful 3–5 year projections? The startup didn't survive long enough to validate them. That sophisticated agent force planning? It was a solution in search of a future problem.

The Reality Check Framework

Finance's job is to drive value-adding decisions for the business through timely, accurate information. That's it.

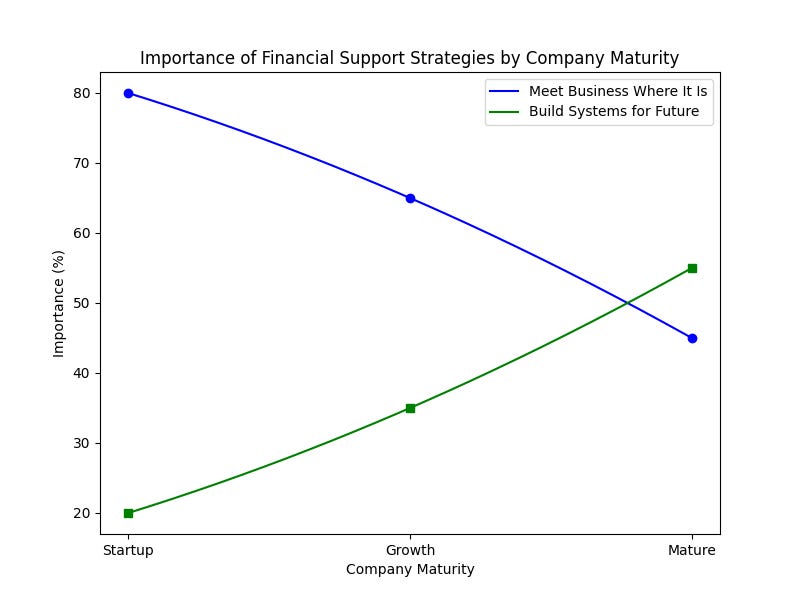

To do this effectively, you need to build support systems that serve the business where it is while keeping an eye on where it's going.

When I work with clients, I ask myself (and leadership) two key questions:

Am I (FP&A) meeting the business where it is?

Are our processes and systems robust enough to support where the business will be in three to five years?

For younger, less mature businesses, the first question is crucial. As businesses grow and scale, the second question becomes increasingly important.

Now, this framework isn't perfect—it suggests a tradeoff between these two priorities. These considerations exist within a broader set of responsibilities (i.e., capital raising, risk management, etc.). Additionally, "meeting the business where it is" remains more ambiguous than my analytical mind would prefer. I'll explore what this means in practice in future articles.

For now, it helps to conceptualize the importance of focusing your efforts in the right place given the situation.

The Art of Ad Hoc Analysis

Here's another subtle but crucial lesson: When the same "ad hoc" question keeps coming up, it's time to standardize that reporting. But don't mistake regular reporting needs for ad hoc exercises.

Common ad hoc scenarios might include:

"What if we cut half the staff?"

"What if we hire an outside marketing agency?"

Your job isn't to avoid these questions - it's to identify which ones deserve to graduate into your standard reporting package. Be picky because the business can change quickly if you don’t strike the right balance between ad hoc exercises and regularly needed insights, you’ll build the wrong platforms.

There's also a flip side to this lesson: It's perfectly fine (especially when the business model is rapidly evolving) for much of the FP&A support to be ad hoc.

I know this sounds sacrilegious to finance professionals, but the truth is ad hoc analysis never truly goes away. If you try to implement frameworks that are too rigid for your business's maturity level, you'll waste precious time building systems that will need to be completely revised within weeks.

The Bottom Line

Want to build a finance function that actually serves your business? Start small, stay focused on cash, and let your infrastructure grow with your actual needs - not your aspirational ones. You can always build more sophisticated systems later, but you can't get back the time you waste building systems you don't need yet.

If you're facing these challenges in your business and want expert guidance on right-sizing your finance function, I'm here to help. Drawing from my experience as both a Fortune 500 FP&A leader and startup CFO, I can work with you to build exactly what your business needs today while positioning it for tomorrow's growth. Schedule a consultation to discuss how we can optimize your finance operations together!